Table of Contents

Calendar of Ashram EventsIn Profile: Daivarata

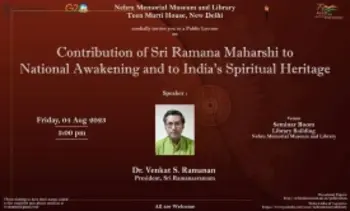

Announcements: Events in Delhi

Sri Ramanasramam’s In Focus

Events in Tamil Nadu: Centenary Celebrations Coimbatore

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Guru Purnima

Origins: The History of the Ashram Tamil Parayana

Bhagavan and Cinema: Harischandra

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Ganapathi Muni Day

Sadhu Natanananda’s Upadesa Ratnavali, 11th Stanza

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: H.C. Khanna Day

Sri Bhagavan’s Ayurvedic Verses: Vadaharam (Couplet)

In Profile: Daivarata

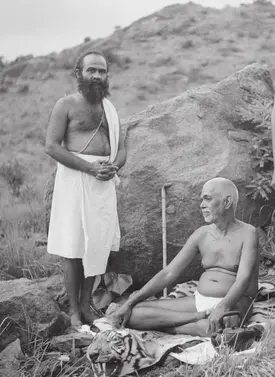

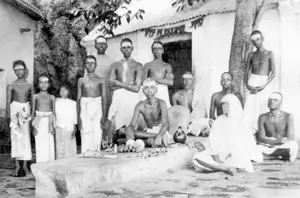

Each one of Bhagavan’s devotees is unique and this also applies to Daivarata who first came to Bhagavan at Skandasramam in 1917 at the age of 25.

Born in 1892 to a family of Vedic pundits from Gokarna, North Kanara District of the Bombay Presidency, he grew up in an environment soaked in scripture and recitation. As a boy, he studied the Rigveda and Taittiriya under the guidance of his father, Vighneswara Bhat Bhadti, a Vedic scholar living the simple life of a farmer. His mother, Smt.Nagaveni, was the daughter of a learned scholar Sri Ganesa Sastry Hosamane and the family followed the tradition their ancestors had carried with them from North India some 800 years earlier when they were brought to South India by the renowned King Mayura Varma.[1]

Named Ganesh after his maternal grandfather, the boy attended classes run by the local Vedic pundits but decided not to follow the priestly profession and instead, aim for higher spiritual ideals. At the age of fifteen he was initiated into bhakti yoga by Ramdas Maharaja of Ujjain who inspired him with devotion and taught him to relish the transformative power born of singing and dancing to classical devotional songs. Ganesh accompanied his teacher along with other disciples on a two-year pilgrimage that took them across the whole of North India and up into Nepal. When their yatra led them to the teacher’s native Ujjain, his beloved guru attained samadhi on the banks of the River Chambal.[2]

On Ganesh’s return journey, he met Tembe Maharaj, the highly revered peripatetic saint monk who perpetually wandered all over India in the traditional way, granting blessing simply by his presence. Expert in Sanskrit, jyotisha and yoga, Tembe Maharaj was highly regarded for his saintliness and extraordinary spiritual attainments. He taught Ganesh pranayama and other traditional yogic practices. Later Ganesh met Kavyakantha Ganapathi Muni when the Muni came to Gokarna to observe austerities. Ganesh was naturally attracted by the Muni’s charisma, ardent faith, and knowledge of the Vedas. In a short time, Ganesh became the teacher’s most coveted student and received the name ‘Daivarata’ after the ancient Rishi Devarata to whose pravara[3] he belonged. The Muni initiated Daivarata into Upanishadic disciplines such as mukhyapranopasana and the vaidica vidya[4] Over many months attending the Muni’s lectures, Daivarata picked up spoken Sanskrit.[5] He renewed his study of the Gita and the Upanishad and in the Muni’s absence, studied the Yoga-Kriyas with Tembe Maharaj. Later he took to a life of penance, living on alms in a little hut on the banks of the Ganges. He lost interest in acquiring endless amounts of book knowledge. He went to Bombay where he stayed for some time and proceeded to Orissa to join the Muni. Once reunited, master and pupil set off for the Mahendra mountains where they observed penance for a month at the Parasuram Tapovana. Next, the master led him to Arunachala to meet and pay respects to his guru, Bhagavan Sri Ramana, where they would spend the next two months. At the first sight of the sage, Daivarata was so moved that verse began to spontaneously pour forth from his lips. He uttered eight Sanskrit stanzas which would later receive the title ‘Ramana Vibhaktyastakam.’[6] The impact of the sage’s presence was so great that Daivarata felt he could grasp the Sage’s teaching without the least confusion just by listening with rapt attention. In speaking of Bhagavan after this first encounter, Daivarata reflected:

On getting Maharshi’s darshan, all the doubts in one’s mind are cleared and one’s desire to know is also fulfilled all at once. This is a sign of his spiritual greatness. His eyes always glitter with spotless light, full of peace and pure love. To sit and gaze at his motionless, peaceful countenance is itself an act of worship. By having his divine darshan, people forget the world. They do not feel the pangs of hunger and thirst. Negative feelings or attitudes such as anger and hatred subside altogether. And people become so much engrossed in his darshan that they do not like to leave his divine presence.[7]

In visits to the Ashram on the Hill, Daivarata could not help but be very impressed by the Maharshi’s continuous and ‘natural communion with God’. He set about to figure out how he might reach such a state.[8] He writes:

Bhagavan has reached the state which is beyond the four varnas and Asramas, and therefore, he is called athivarnashrami. He is firmly established in his Divine state keeping himself free of all thoughts desirable and undesirable, happy and unhappy. Great Pundits, yogis, yatis, ascetics, mahatmas, rajas and maharajas are fascinated by his divine self-knowledge.[9]

Ramana Gita

During an encounter with Bhagavan on 7th July 1917 at Skandasramam, Daivarata posed numerous questions. Ganapathi Muni had encouraged his disciples to clear their doubts with the Sage as he wanted to note down Bhagavan’s responses and include them in the volume of Sanskrit verse he was working on called Ramana Gita. Daivarata who Bhagavan knew as ‘Gajanana’ asked about correct conduct in this world of births and deaths and the means of attaining True Knowledge. As Bhagavan responded to each question, Kavya Kantha noted down the Master’s answers in ‘sutra form’[10] and then very soon rendered them into Sanskrit verse. Answers to Gajanana’s (i.e. Daivarata’s) questions were eventually incorporated into Sri Ramana Gita, Ch.III. The completed work was ready by the end of the year and was translated into Telugu and Tamiḷ[11] and published in 1923.

Daivarata’s first question was: “In this samsara, what is the chief thing a sadhaka must do?”

Maharshi: Well, your question is what you as a person should do in regard to your karma, action. It asks about the most important duty. You wish to arrange duties in the order of their importance, and this importance is based on the value — to you — of the fruits of each karma. In short, you are inquiring into your appropriate karma and the value of its fruits. Does not the karma and its importance depend plainly on the individual who is to perform it and reap the fruit? If so, then, as a preliminary to this investigation, first inquire who the person is that does the karma and tastes the fruit. In other words, take up the inquiry “Who am I?” and inquire into yourself which almost immediately becomes the inquiry into the Self, with a view to Self-knowledge.

Gajanana: Again, Revered Sir, what are the means to attain this Self-realization, and as for the means already suggested, namely, inwardly directed inquiry (pratyagdrishti), how are we to attain it?

Maharshi: The steps to attain Self-realization are these: First, the mind should be withdrawn from its objects, and the objective vision of the world must cease. Secondly, the mind’s internal operations (such as ruminative thinking) must be put to an end. Thirdly, the mind must thereby be rendered characterless (nirupadhika or free of attributes) and must continue characterless; and lastly, it must rest in pure vichara, contemplation or realization of its nature. This is the means for pratyagdrishti or darsana, also termed antarmukham, the inward vision or inquiry.

Gajanana: How long does one have to go on with his niyama (disciplines such as the regulation of food, sleep and exertion)? Is he to adhere to them till he attains Yoga Siddhi? And do they prove useful right up to the end?

Maharshi: Yes, the spiritual aspirant in his ongoing pursuit of yoga is helped by such disciplines. Once he reaches his goal, disciplines drop away on their own.

Gajanana (adverting to the answer to his first question): Revered Sir, as for the goal that is attained by firm, characterless vichara mentioned just now, cannot the same goal be attained by the repetition of mantras?

Maharshi:Yes, if the mantra japa is unbroken and performed with an undeflected current of attention and with due faith, equal success is achieved. Even the mere Pranava Japa would suffice. You see that by such a japa (of either the Pranava or other mantras) the mind is deflected from its operations regarding the objective world. By identifying oneself with the mantra, one attains the Atman.[12]

Sri Arunachala Pancharatnam

S.Narasimhayya (later known as Pranavananda) was present during Daivarata and Ganapathi Muni’s visits up at Skandasramam in July and August 1917. He requested the Muni to compose a song on the guru which he did under the title Guru Gita. Devotees then asked for benedictory verses at which point it was mentioned that Bhagavan had earlier composed a single Sanskrit verse in arya metre beginning with “karuna purna sudhabdhe”. Hearing this, Ganapathi Muni asked Bhagavan if he would be willing to compose four more verses which would, along with the first, form the five benedictory verses to the “Guru Gita”. Bhagavan wrote the additional verses and Daivarata penned a concluding verse. The five from Bhagavan and the final verse from Daivarata came to form the Sanskrit Arunachala Pancharatnam which was later translated into Tamiḷ by Bhagavan. The Tamiḷ version is still sung today as the concluding part to the Monday evening Tamiḷ parayana.[13] Daivarata’s verse reads:

This is Sri Ramana Maharshi’s vision of Arunachala in the language of the Gods. It is a jewel of five verses in Arya meter, and indeed contains the essence of the Upanishads.[14]

Padaiveedu Outpourings

After two months with Bhagavan Ramana, the Muni and his disciple went to Padaiveedu, (near Vellore) to continue their sadhana. One day, Ganapathi Muni heard Daivarata muttering while in a deep state of meditation. When the same thing happened the following day, the Muni realized that the utterances were Vedic in nature and were in Vedic meters. Ganapathi Muni began taking notes. These daily occurrences lasted three hours and went on for about sixteen consecutive days.

The verses are in four Vedic meters, namely, Gayatri, Anushtubh, Trishtubh and Jagati, and ‘invoked forty-two Vedic deities of which Saraswati, identified with Vak, the Goddess of Speech, was predominant.’[15] The commentary adds that ‘none of these mantras were traceable to any known Vedic source.’

In his commentary, the Muni said that some of the mantras could not be noted down simply owing to the rapidity with which they were uttered. Others were not sufficiently distinct. Only those which were complete and clearly audible, and which could be taken down in full were compiled. Some fifty suktas (hymns) with 448 stanzas were noted.

K.Natesan later commented on the humility of Ganapathi Muni who took the trouble to note down the utterances of his young student. But the Muni recognised the greatness of these verses that came forth spontaneously from his pupil’s lips in a recurring darshana of chandas, a vision of Vedic mantras. Natesan writes:

The Guru of the disciple, our Ganapathi Muni, acted as scribe and noted down the mantras as they issued forth from his inspired disciple. Later, the Muni even wrote a commentary on the mantras just as Adi Sankara had done for the verses of his disciple Hastamalaka.[16]

The mantras were so remarkable that Ganapathi Muni used the word ‘supersight’[17] to refer to his disciple’s enunciations which seemed to suggest inspired contact with the Goddess Vak. The commentary by Ganapathi Muni includes Daivarata’s birth chart on which the Muni is well-qualified to comment given his formidable understanding of jyotisha. He comments that the rasi contains combinations and alignments (yogas) that would suggest ‘greatness’.[18]

Bhagavan the Mountaineer

After the experiences at Padaiveedu some years passed until Daivarata saw Bhagavan again in the mid-1920s. Later during the Jayanti celebrations of 1936, GVS submitted his Telugu verse translations of Ramana Chatvarimsat (‘Forty Verses in Praise of Ramana’) and notes that he had already sent the Ashram a rendering of Ramana Vibhakti Ashtakam (“Eight Grammatical Cases in Praise of Ramana”) authored by Daivarata. While scrutinising the two works, Bhagavan said that Daivarata had originally described him in the first of his eight verses as a “Mountaineer” (Parvathiyah) whereas Nayana urged him to change it to “the son of Parvathi” (Pārvatya:).[20]

Bhagavan also mentioned to those in the Hall that Daivarata was living in Nepal and was held in high esteem as “Maharshi Gajanan Sarma.” A visitor had recently asked Bhagavan where Daivarata was. Even as Bhagavan was replying that his whereabouts was not known, the day’s mail was handed to Bhagavan, and the very first letter was from Maharshi Gajanan Sarma of Mukthi Kshetram, Nepal. In it he had written that though he was so far away, he always felt that he was only at the feet of Bhagavan. As if to bring home that feeling, the letter enclosed a photograph of Daivarata with a flowing beard. Bhagavan added that it struck him at the time as if Daivarata himself appeared in person and answered the query, saying “Here I am!”[21]

It was also in 1936 when Daivarata lost his two first gurus. Both Tembe Maharaj and Ganapathi Muni left the body that year. Daivarata had always been grateful to Ganapathi Muni for having brought him to Bhagavan.

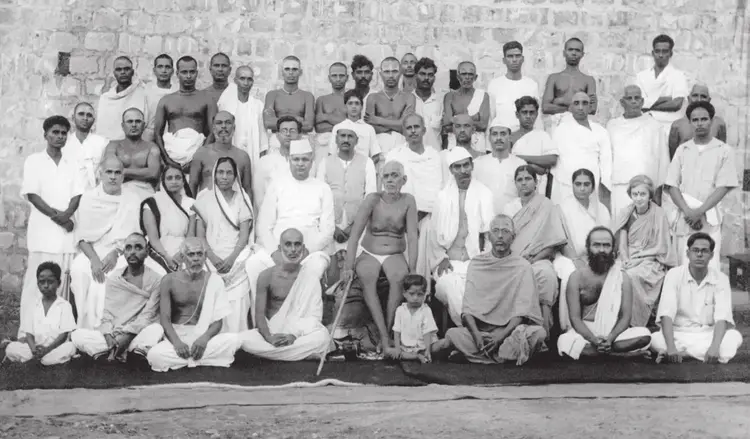

In August 1938 Daivarata met Gandhiji along with Dr.Rajendra Prasadji and Jamnalal Bajaj in Bombay and on Gandhji’s request, the three went to see Bhagavan to seek his blessings. Group photos were taken of the party and other devotees together with Bhagavan behind the darshan hall.

Daivarata’s Visit in 1946

Daivarata next visited the Ashram in February 1946, still ‘looking sturdy and strong’. After parayana, Bhagavan recounted the history of Daivarata’s visits to Tiruvannamalai starting with Skandasramam in 1917.

At breakfast, Bhagavan enquired where Gajanana, i.e. Daivarata, was staying and what he was going to take. It was reported Gajanana had gone for his bath. Bhagavan then said, “He can eat anything. If you give him a quantity of tender margosa leaves and a chembu of cow’s urine, he will breakfast on that. He had lived on things like that during his years of wandering.”

About 10.30 a.m. Gajanana was in the hall showing a picture of a Pasupati image in Nepal and explaining its esoteric significance. Later that day, Gajanana was telling Bhagavan about Nepal. He said, among other things, ‘There are three important shrines in Nepal, all very sacred. The King is a very religious man, and it is the custom and tradition there for the King not to do anything or go anywhere without first going and taking permission from the gods in these temples.’

Balaram Reddy said to Bhagavan, “He does bhajan with great spirit and enthusiasm. We should have it one day here.” When asked, Gajanana expressed his willingness. “Can we get some tinkling beads for the ankles and some accompaniment?” Bhagavan also said, “He must have some sruti like harmonium, some accompaniment like mridangam or ganjira and some cymbals (jalra).” Balaram Reddy asked if Gajanana had performed bhajans while walking on pradakshina. Bhagavan replied, “Oh, he would do his bhajan while walking. He would jump from one side of the pradakshina road to another. He was so full of life and enthusiasm.” Gajanana said, “I was much younger then. But I can do it even now.” Discussing where and when such a bhajan should be arranged, it was decided that it would be better in the dining hall.[22] When all was arranged, Bhagavan sat where he usually did at mealtime while devotees all sat in rows. Daivarata began singing and dancing up and down the rows with great enthusiasm. He also sang Ganapathi Muni’s Chatvarimsat in his own melody, dancing to the tune.

Conclusion

After Bhagavan’s Mahanirvana, Daivarata built his own Ashram near the seashore outside of Gokarna and established a Veda patasala there with about 20 students. One day a rogue wave came roaring in and took away every last building. Daivarata’s response was looking placidly heavenward, saying, ‘the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away.’ He rebuilt a little further inland on the large property and settled into a quiet rural life which he felt blended perfectly with the sacred culture of the Vedas. This didn’t keep dignitaries away such as Lal Bahadur Shastri, the second Prime Minister of India and Maharshi Mahesh Yogi among others.

Daivarata shied away from public life and said that agriculture and caring for the cow who so generously provides for our needs were the two fundamental vocations directly connected with a meaningful earthly life. He became versed in herbs and natural ways of eating for spiritual and health benefit. He promoted harmonization of the mundane and spiritual life as something that is not only possible but also the most ‘fruitful, integral, and meaningful way of life propounded by the Vedas’.[23]

Sri Ramanasramam's In Focus

During the pandemic, devotees were stranded in their homes and had no access to Bhagavan’s Ashram. There was an intense demand for video footage of the Ashram, especially considering that pujas and recitation in the Ashram continued unabated throughout the pandemic even if the Ashram was closed to the public and virtually no one was in attendance. It was only reasonable to video record as many Ashram functions as possible and make them available to devotees. During this period, In Focus was inaugurated (March 28, 2021) and weekly editions were uploaded for the next 18 months until August 2022. From September to December that year, In Focus began to be released once every two weeks. When Tamil Parayana Live started, it was thought that In Focus would no longer be needed. But the demand was great, and the Ashram reinstated the series in January 2023 as a once monthly release. Please see these tastefully edited monthly videos featuring daily life in Sri Ramanasramam. The

June and

July editions are available on

Sri Ramanasramam's ![]() channel.

channel.

Events: Ramanasramam Centenary Celebrations, Coimbatore, TN

On 16th July 2023, Ashram President, Dr.Venkat S.Ramanan attended the Sri Ramanasramam Centenary Celebrations in Coimbatore. The theme of his talk was satsang wherein he said: ‘We are part of a bigger family and live in a world where the feeling of family prevails. An organisation is nothing more than a sum of its parts and we are the sum of such great devotees that I am proud to be the president of such an organisation. After all, nowhere do we find such spiritually minded people. When Ganapathi Muni asked Bhagavan what the goal of society was, Bhagavan said that it was “universal brotherhood based on equality”. We know that in the external world we can never reach perfect equality, but Ramana devotees know that within, we are all equal, all the divine Atman, all elements of the eternal satchidananda. The advantage of satsang is that we meet like-minded people and get a compounding effect. As my grandfather, Venkatoo, used to say, “whenever I go anywhere, Bhagavan is there before me already waiting for me”. This applies to all of us.’ The President then quoted Prof.K.Swaminathan’s translation of Guru Vachaka Kovai where Sri Muruganar writes on the theme of satsang: The best friendship is with those good men whose minds are dead and who abide in the pure silence of awareness and hereafter live in the company of sages steadfast in their state of moveless stillness.

Origins

The History of the Ashram Tamil Parayana

Devotees often think that Bhagavan only taught atma vichara and surrender and that he only wanted us to practise these at the exclusion of all else. But Bhagavan also prized the recitation of sacred texts. This is made evident at Skandasramam when Bhagavan initiated chanting of the Ribhu Gita and other advaitic texts. He held the hymns of Sundarar, Appar, Jnanasambandar and Manikkavachagar in high esteem and encouraged the recitation of his own poetic compositions.

In 1917 at Skandasramam when answering a devotee’s question, Bhagavan said that if our recitation is ‘unbroken and performed with an uninterrupted current of attention and with due faith’, and if in the process ‘the mind is deflected from its operations regarding the objective world, one will attain the Atman.’[24]

This complements what Bhagavan would later state in greater detail when extolling the efficacy of listening to the teaching. Bhagavan says:

The effects of sravana may be immediate and the disciple will realise the truth all at once. This happens only for the well-advanced disciple.[25]

In other words, hearing the sacred teachings of the master is an ‘aid for eradicating thoughts and the predispositions remaining in seed form’[26]. Bhagavan explains:

Here we have Bhagavan’s teaching in a nutshell which, to be sure, includes surrender and inquiry (nididhyasana) but does not neglect hearing (sravana) and reflection (manana). The starting point would seem to be with hearing and learning the teaching. Only then can the diligent devotee put it into practice.

For the sadhu-devotees gathered round Bhagavan up at Skandasramam in 1917, the benefits of the study and repetition of Bhagavan’s poetic works was self-evident. If tradition says that Saraswati, the goddess of speech (Vak Devi), endows human beings with the power of wisdom, learning, and speech, then the place to begin is with recitation. Thus, they started regular parayana.[28]

Kunjuswami once said that when he first came to Bhagavan in 1920, Bhagavan’s mother was in the habit of reciting devotional songs each morning between 4 am and 5 am. When she completed her recitation, other devotees would chant Sri Arunachala Aksharamanamalai, Appalap Pāttu and Bhagavan’s Tamil rendering of Sri Dakshinamurti Stotram, among others. In the course of time, Bhagavan composed new works, which were incorporated into the daily chanting repertoire. By the late 1940s, the parayana cycle had grown to fifteen days and consisted of more than thirty works. The recitation was as follows:

Day 1: Tiruvannamalai Devaram, verses in praise of Arunachala by Jnanasambandar, Navukkarasu and Sundaramurti;

Day 2: Sri Arunachala Tattuvam, Sri Arunachala Mahatmyam, and iAkshara Mana Malai;

Day 3: Sri Arunachala Nava Mani Malai, Sri Arunachala Padikam, Sri Arunachala Ashtakam, iAppalap Pāttu, and Anma Viddai;

Day 4: Upadesa Undiyar and Upadesa Saram in Malayalam, Telugu and Sanskrit;

Day 5: Ulladu Narpadu and Supplement to Ulladu Narpadu; Day 6: Sat Darshanam (the Malayalam version of Ulladu Narpadu and its Supplement);

Day 7: Devikalottaram;

Day 8: Anma Sakshatkaram, Sri Guru Stuti, and Sri Hastamalakam;

Day 9: Gita Saram in Tamil, Malayalam and Sanskrit;

Day 10: Anma Bhodam and Ekanma Panchakam;

Day 11: Dakshinamurti Stotram in Sanskrit and Tamil and selected verses in Sanskrit and Tamil from Vivekachudamani, Sivananda Lahari and works of Thayumanavar;

Day 12: Sri Ramana Stuti Panchakam by Satyamangalam Venkataramayyar;

Day 13: Sri Ramana Deva Malai and Satguru Malai by Sivaprakasam Pillai;

Day 14: Sri Ramana Deva Malai and Vinnapam by Sivaprakasam Pillai;

Day 15: Ramana Pada Malai by Sivaprakasam Pillai and verses on Tiruchuzhi by Manikkavachagar and Sundaramurti.

The above liturgical corpus began to take shape in the years at Skandasramam and can be divided into four main categories: the original works of Bhagavan in Tamil, Telugu, Sanskrit and Malayalam; works translated by Bhagavan from Sanskrit into Tamil and Malayalam; verses selected by Bhagavan from classical Tamil and Sanskrit texts; and works on Sri Bhagavan by devotees.[29] Reciting these verses each evening became a regular practice and many of these continue to be recited in the present day.

Bhagavan and Cinema: Harischandra (in Tamil with English Subtitles)

In the last issue, we received the link for the newly uploaded Mirabai (starring M.S. Subbalakshmi) a film which Bhagavan viewed on 5th Nov. 1946. This supplements links for the previously uploaded Nandanar (part 1, part 2) and Sant Tukaram (part 1, part 2). Since then, devotees have edited and uploaded the Tamil film Harischandra (part 1, part 2) with English subtitles. This film was viewed by Bhagavan on 1st November 1946. Owing to some delay that night, the film could not be started until 9.30 pm which meant that Bhagavan had to stay awake till 12.30 am. Nevertheless, he sat through it all and Devaraj Mudaliar says, ‘he seems to have enjoyed it’ (Day by Day, p. 338)

Editor's note: Ashram devotees are hoping to locate copies of the Hindi films Karna and Bhartruhari as well as the Tamil film Bhakta Pundarika, films seen by Bhagavan. If anyone has information regarding any of these, please write to the Ashram President at posrm@gururamana.org or to mhighburger@gmail.com

Earliest Beginnings to the Present

In the early days of the Tamil parayana, the works composed or selected by Bhagavan were compiled in a notebook and those wishing to chant them would copy them out by hand. On occasion devotees would request Bhagavan to copy them out himself for their use and he spared no pains in heeding their requests. One such notebook was obtained from one of Bhagavan’s attendants, Swami Sivananda, and published by Kanvashrama Trust in 1987. Subsequently Kanvashrama Trust made selections from the text and a devotee, the late Smt. Shanta Gurumurti, helped in rendering them in Roman transliteration. This book was published in 1998 and has served as the principal chanting text for those unfamiliar with Tamil. In 2006 a parallel text of Tamil transliteration with English translation was published. The following year, a similar parallel text with modern Tamil was released.

In 1985 daily Tamil parayana in Ramanasramam was initiated by Anuradha Jambunathan under the supervision and guidance of Kunjuswami. The current programme of Tamil recitation at the Ashram follows the sequence established in the Tamil Collected Works.

Monday Parayana

The hymns in Sri Arunchala Stuti Panchakam are among the earliest of Bhagavan’s compositions. They were written around 1914 when Bhagavan was living on the hill at Virupaksha Cave. The Arunachala Mahatmyam,[30] a short hymn that introduces Sri Arunachala Stuti Panchakam, is taken from the Skanda Purana and was translated by Bhagavan into Tamil. Included in this prelude are verses on the significance of Arunachala written by Muruganar and a verse by Bhagavan on the significance of the beacon flame atop Arunachala on Deepam Day.

Among his devotees at the time of composing this hymn were several sadhus who used to go to town each day to beg for alms. It so happened that other sadhus in town would try and give their benefactors the impression that they too were connected with the Maharshi in order to improve their chances of receiving alms. Devotees requested Bhagavan to compose a song that they could sing while on their round for bhiksha, both as a way of benefiting their patrons with Bhagavan’s wisdom and to distinguish themselves as his devotees. Initially Bhagavan declined, saying that there were already plenty of songs by the Saivite saints. But they continued to press him, and in the end, he relented, composing the Akshara Mana Malai or the ‘Marital Garland of Letters’.[31] The second, third and fourth hymns (Sri Arunachala Nava Mani Malai, Padikam and Ashtakam) were written about the same time. Whereas later poems of the Maharshi are teaching-oriented, these hymns are soaked in devotion. Sri Arunachala Nava Mani Malai, like Akshara Mana Malai, tells of the wonder of Arunachala.

Of Sri Arunachala Padikam[32] and Sri Arunachala Ashtakam Bhagavan said:

The only poems that came to me spontaneously and compelled me, as it were, to write them without anyone urging me to do so are Sri Arunachala Padikam and Sri Arunachala Ashtakam. The opening words of Sri Arunachala Padikam came to me one morning and even though I tried to suppress them, saying, “What have I to do with these words?” they would not be suppressed till I composed a song bringing them in; and all the words flowed easily, without any effort. In the same way the second stanza was made the next day and the succeeding ones the following days, one each day. Only the tenth and eleventh were composed the same day.[33]

Arunachala Pancharatna

For a description of the genesis of the fifth hymn, Arunachala Pancaratna, see above which tells how the five verses came to be composed by Bhagavan in Sanskrit (with a concluding verse by Daivarata), all of which were translated by Bhagavan into Tamil for inclusion as the closing verses of the Arunachala Stuthi Panchakam.

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Ganapathi Muni Day

Sadhu Natanananda’s Upadesa Ratnavali, 11th Stanza

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: H.C. Khanna Day

Sri Bhagavan’s Ayurvedic Verses: Vadaharam (Couplet)

[1] Private conversations with members of the Gokarna community

[2] Called Charmanvati in Mahabharata

[3] The same family line (gotra)

[4] Central life worship and deep knowledge of the Vedas

[5] 'The Insight of Chhando-Darshana: Biography of Sri Brahmarshi Daivarata', translated from the Kannada and published in 2019. See also <brahmarishidaivaratha.com

[6] see archive.arunachala.org for the sanskrit verses.

[7] Arunachala Ramana, Boundless Ocean of Grace, vol I, p. 459-461

[9] Ibid.

[10] sutra - brief aphoristic phrase

[11] S.Narasimhayya was later known as Pranavananda.

[12] This prose version of Chapter 3 is from B.V.Narasimha Swami. For the complete text see the Sep/Oct 2009 issue of 'The Maharshi' newsletter

[13] The concluding verse beginning “srimad ramana maharshe” was written by Gajanana.

[14] Recited during the Tamiḷ Parayana: see 'The Poetic Works of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi' as: This Arunachala Pancharatnam revealed by Sri Maharshi in Sanskrit is the very essence of the Upanishad.

[15] These details are narrated in Chhandodarśana by Daivarata (1968); publication found in the archive.org by Kapre. The book includes Daivarata’s verses and an introduction and commentary by Ganapati Muni

[16] see https://kavyakantha.arunachala.org/ by Guruprasad Madhavan

[17] Chhandodarsana is vision (darsan) of verses in vedic metre (chhanda

[18] Living Mantra: Mantra, Deity, and Visionary Experience Today, Mani Rao

[20] It is interesting to note that the published version retains parvatiyah or ‘mountaineer’ and reads, śrīmat parāśaroyam pramuditavadanah pāvanah pārvatīyah.

[21] G.V.Subbaramayya’s Sri Ramana Reminiscences, p.8

[22] Day by Day 13-2-46 Morning

[23] brahmarishidaivaratha.com

[24] See this issue's In Profile: Daivarata; Ramana Gita and Sri Ramana Gita, Ch.3

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Parayana refers to recitation of prayers, sacred hymns, poems or songs, often learned by heart. What follows is taken from 'Parayana: The Poetic Works of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi'

[29] Most of Bhagavan’s verses and translations utilise venba metre, consisting of two couplets connected through a link word. A venba contains four lines, the first three of which contain four words each and the last, three words. Bhagavan wrote kalivenba versions for most of his verses wherein the ordinary venba verse is connected to the next verse with a link word to facilitate rote learning.

[30] Verses 5 and 6 are translations of the Sanskrit slokas Bhagavan discovered one day at Virupaksha Cave in the Arunachala Mahatmyam. Bhagavan put the slokas to use as the principal means of declining a request to adopt sannyasa diksha made by a visiting Mutt pundit.

[31] With a few exceptions, the first letters of each of the 108 couplets are in alphabetical order (according to the Tamil alphabet). The first verse, called payiram, is written by Muruganar and is in viruttam metre.

[32] Padikam means ‘ten stanzas’ but in the end this hymn came to total eleven and is often referred to as the ‘Eleven Verses to Sri Arunachala’. Ezhu seer viruttam (seven-word metre): These are eight-line verses with the first line of each couplet having four words and the second, three.

[33] Ramana Maharshi and the Path of Self-knowledge, Arthur Osborne, 2004, p. 205