Table of Contents

Calendar of Ashram Events

In Profile: Swami Abhishiktananda

Bhagavan’s Handwriting: ‘Decad of Miracle’ (v.10)

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Tamil New Year

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Major Chadwick Day

Ashram Veda Patasala: Examinations at Kanchi Puram

Announcement: Daily Live Streaming

Upgrading the Ashram Dispensary

Sri Bhagavan’s Ayurvedic Recipes: Sukha Virechanam

Events in Ramanasramam: Bhagavan’s 73rd Aradhana

Announcement: Mahapuja, 12th June 2023

In Profile: Sw.Abhishiktananda

Henri Le Saux

Among the diverse devotees that appeared from around the world to sit at Bhagavan’s feet in the darshan hall, Henri Le Saux was not your run of the mill Western seeker. When he came to the Maharshi in January 1949, he had already been a Benedictine monk for twenty years.

Born to a pious family in Brittany, he was reared in the orthodox observances of pre-Vatican II Catholic France. In 1934 when already in his fifth year in the monastery of Sainte-Anne de Kergonan, he had the growing sense that the monastic life should more effectively centre on an intimate encounter with the Divine. With great vigour the desire to come to India and seek the inner life rose up in him.

For Le Saux, Western culture’s growing fascination with the East was understandable, born of a crisis in the collective heart and a dearth of any personal encounter with faith. Since the Middle Ages Christianity seemed to have lost its mystical edge, lost sight of any authentic meeting with the divine from the inner recesses of the heart. It was in danger of becoming irrelevant in a rapidly changing modern world. Le Saux was astonished to see how the faith traditions of India had managed to keep alive and at the centre of their creed and practice the contemplative dimension right up into the 20th century.

Some moral problems can only be resolved through interiority and private prayer, he mused, and no quantity of good intentions can assist the Christian seeker in fulfilling the categorical imperative of loving unconditionally if he continues to be governed by his narcissism. And yet, how to come free of it?

For Le Saux, the Western crisis had become more acute in a century dominated by war and the facile consumerism that followed. If the Church’s religious truths had been unable to keep pace with history, it was owing in large part to the fading away and flickering out of the contemplative fire of the direct experience of God. Where might one go to recover the flame?

Born in St. Briac on the north coast of Brittany, Le Saux was the first of seven children. His father had been crippled by a war injury but despite his disability, made the long walk each morning to the local parish Church, earning him the local reputation as a saint.

His mother and siblings were likewise devout and Le Saux discerned from early on a calling to the priesthood. At the age of ten, he attended the Minor Seminary at Chateaugiron and then at sixteen, the Major Seminary at Rennes. During this period, he began to correspond with the Abbey of Sainte Anne de Kergonan and eventually applied to enter as a candidate for full monastic ordination.

In 1929 at the age of nineteen he entered the novitiate. By 1934 in his fifth monastic year during which time he served as monastery librarian, he took to reading books on India and openly expressed his longing to go there.

This inquiry was interrupted in 1939 when he was called into mandatory military service and was soon conscripted as a soldier during the war. When his unit was surrounded by enemy troops and was forced to surrender, he escaped and made his way back to the monastery.

Le Saux, who would later take the sannyasin name, Abhishiktananda resumed the long and arduous process of seeking exclaustration, a Canonical procedure wherein official authorization to live outside his religious community might be obtained from the Vatican. As a solemnly professed Catholic monk, Abhishiktananda was bound by his vows, though now in a modified form, and would be permitted to travel to India for the purpose of establishing a monastic community in a ‘completely Indian form’.[1]

When it was made clear, however, that his intention was centred on the purely contemplative dimension, the initiative met with resistance.

After the war, Abhishiktananda corresponded with Bishop Mendonca of Tiruchirappalli and another French priest, Jules Monchanin who had been living in South India since 1939. He wrote to Monchanin:

I have had this dream for over thirteen years, and in recent years it has been continually in my thought and prayer. Two years ago, I received my Father Abbot’s permission to put out a certain number of feelers in this direction. I was given much encouragement, but as soon as the moment came for taking action, problems were raised, and the offer of help was withdrawn.[2]

On 26 July 1948 when at last all formalities and bureaucratic hurdles had been overcome, Abhishiktananda boarded a steamer and set sail for the East. Once at sea, he breathed a sigh of relief, and simultaneously brimmed with excitement, on the brink of something outstanding, something singular in its promise for a new way of living out his monastic vocation. If he wondered what had prompted him to take the radical step of taking leave of his brothers at the Abbey to go and live in a country he had never visited, he intuited that India had the potential to shepherd him down the path he had longed to follow since his boyhood. As the months and years unfolded, what India could offer the genuine seeker became increasingly apparent. He later reflected:

India’s [great] privilege and her glory [is] that she pursued her spiritual and philosophical quest for Being to its ultimate depths. In so doing she made [humanity] aware of [its] own deepest centre, beyond what cultures termed ‘mind’, ‘soul’, or ‘spirit’. At this transcendent point her sages discovered God, or rather, the divine mystery, beyond all its actual or even possible manifestations, beyond every sign which claimed to represent it, beyond all formulations, names, concepts, or myths. At the same time, they discovered their own true self to be likewise beyond everything that signifies it, whether it be body or mind, sense-perception or thought, or that which is normally called consciousness. It was this awareness that gave rise in India, for the first time in the history of the world, to the phenomenon of monastic renunciation (sannyasa). Men heard the call to total renunciation and abandoned the world and human society to live in mountains and deserts, to wander ceaselessly from place to place, in silence and solitude, stripped of everything.[3]

To what extent Abhishiktananda was aware of the deeper reasons that he was being drawn eastward is not clear. But he didn’t need to know anything more than every intuition pointed to South India. On 15th August 1948, the first anniversary of India’s Independence, Abhishiktananda disembarked at Colombo:

Yesterday evening we arrived off Colombo. Such joy and emotion! Immediately after supper ... I went up on deck and began Vespers ... my eyes fixed on the East. The sun had already set, and ... I saw a sudden gleam of light, the harbour lighthouse of Colombo. One by one other lights appeared beside it, and soon the horizon was twinkling with myriad points of fire, a symbol of all those who are waiting and calling. At about 8 pm we dropped anchor in the harbour. I was glued to the ship’s rail; people tried to talk to me, but I could only answer with difficulty. The crescent moon was reflected in the black water, stars were few and the night was dark. I had been waiting for this moment for fifteen years![4]

Once in India, Abhishiktananda reported to the Bishop of Tiruchirappalli and met the French priest, Jules Monchanin, who he had been corresponding with and who he described as ‘profoundly unworldly’, ‘magnificently learned and capable of marvellous intuitions’ even if impractical. He learned that Monchanin had met the sage Ramana Maharshi more than once. Abhishiktananda had read about the Sage in France and had long wanted to see him. The two regularly discussed Sri Ramanasramam. To their surprise, the bishop proposed they go to Ramanasramam and stay for some time. Thus only a few months after arriving in India, in the third week of January, the two priests went to Tiruvannamalai. Little did Abhishiktananda know that this meeting would redirect the course of his life. He narrates in the tone of a travelogue which would soon turn to personal testimony:

Like the other pilgrims to Arunachala, we hired a bullock-cart and squatted down at the back of it as well as we could, on a truss of hay. We travelled thus with much jolting for a good half- hour, until at last we reached the gateway of the ashram. As soon as we arrived Purushananda (Monchanin) was recognized by some of the Brahmins in the ashram. Sri Raja Iyer, the genial and helpful postmaster at the ashram, at once busied himself with finding us a room, and saw that we were breakfasted and given a chance to rest, while awaiting the time for darshan.[5]

Abhishiktananda lost no time in learning of recent events in the community:

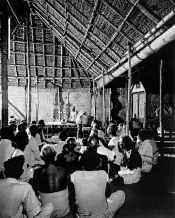

In recent months darshan had been given in a kind of large open shelter, supported on bamboo poles and covered with coconut leaves, a pandal, as these temporary structures are called in South India. This pandal had been erected for the golden jubilee celebrations of the Sage’s arrival at Tiruvannamalai. After that it was retained and adapted for the darshan, as the small hall which the Maharshi had been using until then had become too small for the growing flood of visitors and pilgrims who came to the ashram.[6]

The two travellers rested in the morning and then proceeded to the Hall. It was Wednesday 24th January 1949:

On entering the pandal, one saw at the other end the Maharshi installed on his couch, sitting up and usually supporting his elbow on his bent knee, enveloped in the smoke which rose from the incense-holder and sticks of burning sandalwood. Around him stood three or four specially chosen disciples, on the watch to respond to his slightest gesture; it was also their business to receive the offerings of fruit and cakes as they were brought in, and to distribute them to the people present, once the touch of the Sage’s hand had transformed them into prasad. Between this ‘sanctuary’, so to speak, and the assembled crowd, there was a balustrade. Beyond this, in the main hall, were seated the men; and to the right of the Maharshi, the women sat in a kind of annexe. Most of them were wearing brightly coloured silk saris, and kept their eyes fixed on him.[7]

The monk-priest continues to describe the scene:

A solemn silence prevailed in the pandal, scarcely disturbed by occasional discreet whispers. Whenever Sri Ramana said anything to one of those around him, everyone listened eagerly; most often he was merely asking for a book or for the bottle of oil with which he rubbed his joints, as he was troubled with rheumatism. The faithful, seated on the ground, either gazed fixedly at him, or else kept their eyes shut, absorbed in deep meditation. New arrivals advanced as far as the balustrade joining their hands above the head in the striking gesture of anjali, and then prostrated, face to the ground. After this formal entry they took their place among the congregation.[8]

Abhishiktananda’s moment had at last arrived:

Purusha and I thus entered the hall in our turn, saluted the Maharshi respectfully with joined hands, and took our seat among the crowd. First, I concentrated on looking with deep attention at this one about whom I had read and heard so much. This visit could not fail to be a high point in my life. Since the moment when it had been decided upon, I had looked forward with eager and growing impatience to the hour when I should have the opportunity of being in the Maharshi’s presence. Something had to take place, when once a physical contact was established between myself and him. Of that I had not the slightest doubt: this man had a message for me, a message which, if not conveyed in human words, would at least be spiritually communicated; for, as it had been clearly explained to me, spoken words were the least important of the ways by which the Sage communicated his experience.[9]

However, despite his most fervent expectation, ‘or rather, because of it’, Abhishiktananda ‘felt let down’. But then:

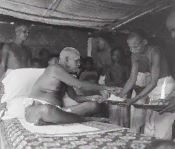

In all that I was seeing and hearing there was something that really stuck in my throat First, there was the ‘liturgical’ atmosphere of the proceedings.... I thus continued to gaze intently at this old septuagenarian, with his gentle face and beautiful eyes. What, was there more to him? His complexion was fair, of a golden bronze tint. His body was bare, as is the custom among true ascetics, apart from a narrow strip of cotton worn as a loincloth. He was sitting on his couch with his legs extended, though sometimes he drew one up and rested an outstretched arm on his knee—a posture which seemed to be a favourite of his. Sometimes he read a book or a magazine, sometimes he corrected proofs from the press, sometimes he listened to what appeared to be the reading of his mail, occasionally expressing agreement with a nod of the head. Surrounded by this ritual, these prostrations, the cloud of incense, and the crowd of people sitting silently with their eyes fixed on him, he seemed so natural, so ‘ordinary’, a kindly grandfather, shrewd and serene, very like my own, as I remembered him from my childhood. I did know what to make of him. Of course, I found all this profoundly interesting, as it was all quite new to me. Besides, this gathering of devotees, their attitude and recollectedness, made quite as deep an impression on me as did the person of the Maharshi. Some of them seemed to be established in an extraordinary state of inner concentration.[10]

Purushananda introduced himself, reminding the Maharshi of his two earlier visits. Then he introduced his travel companion:

The Maharshi replied with a gesture of the hand, accompanied by a smile filled with a kindness that was impossible to forget.[11]

Once in a seated position, Abhishiktananda began to take in the whole gathering and took notice of who was in the hall. He discovered that there were a few Westerners in the crowd, a young Englishman, dressed in the robes of a Buddhist monk, a Swede, and especially one youngster from North India, whose ‘face wonderfully reflected the intensity of his inward gaze.’ Then the hour of lunch arrived:

At eleven o’clock the gong sounded for the meal. Following behind, we all made our way to the refectory. This was a large hall, and on high days could be filled several times over when the pilgrims are fed. There was a mobile partition which separated off the Brahmins. As for Bhagavan, he took his meal with the common lot. He sat back to the wall while we, his guests, were placed in parallel rows at right angles to him. Purusha and I, as this was our first meal, had the privilege of being seated exactly in front of him. Naturally, all the time I was eating, my eyes scarcely ever left him, so eager was I to discover his secret. He was sitting on the floor just like us, ate with his fingers from a plantain leaf as we did, and had the same food as ours. This was a principle that he maintained inflexibly. Since the beginning of his tapas, he had always vehemently refused to touch anything that could not be shared with all and sundry. Sometimes he made a remark to those serving the food, no doubt commenting on its quality or its source, and he seemed to be eating with a good appetite. Once again and without doubt, I could see him as an excellent grandfather. But was there a halo? In vain I strained my eyes trying to see it; all my efforts were useless.[12]

The entirety of the Ashram experience and encountering the Sage was unfathomable and indecipherable for this monk who had spent all his life in the north of France and the previous twenty years cloistered within a few buildings in a rural monastery. The second encounter took place later that day:

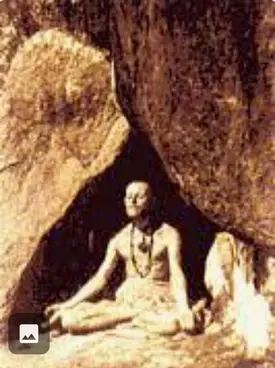

In the afternoon we returned to the pandal. About 5 pm [Vedic pundits] came and sat round the couch on which Bhagavan was seated and began to chant the Vedas—a custom that is still faithfully observed to this day. This was the first time I was hearing that entrancing psalmody with its strong rhythm and its simple melody within a range of only three or four notes. It carries one far back in time to the forest-hermitages of the ancient rishis. At evening, when the sun disappeared behind the horizon and the sacrificial flame rose from their altars, they used to sing these very same verses and taught them to their disciples as a sacred trust for future generations of believers who would take their place in an endless succession on the soil of Bharat. How far I felt myself from that everyday world in which I had been involved only a few hours earlier, from the crowds thronging the trains and railway-stations through which I had struggled to make my way during the previous night. These Vedic hymns, even when their outward meaning escapes one, have a uniquely penetrating power, at least for anyone who allows himself to be inwardly open to their spell-binding influence. We could say that, as they issue from the archetypal sources of being, so they irresistibly draw those who chant them, and equally those who hear them, into the same most secret sources of being. The mind thus finds itself carried off as if to an unknown world, a world in which however it has a marvellous sense of belonging, a world which is revealed in its very source, and yet which seems to disappear as soon as one attempts to define it in rational terms. I quickly gave up trying to understand it, and simply allowed myself to be held and carried along... Even more strongly than the banks of the Kaveri, for all their grandeur, Arunachala was beginning to claim me for itself.[13]

Thus, the monk concluded his first day at Sri Ramanasramam. But he woke the following morning with a fever. Though he did not recognise it at the time, this was an indication that something was truly at work deep within him. Though not well, he was unable to allow himself to miss darshan. Preceded by the chanting of the Vedas, he basked yet again in the bliss of their resonance:

I allowed myself to be carried away by their spell; and I tried more than I had on the previous evening to penetrate behind the eyes of the Sage who was there before me, to find out his secret... After the midday meal Purusha took me to meet Miss Ethel Merston, whom he had met on a previous visit. She asked for my impressions, and as I did not wish to conceal the truth, I told her of my disappointment. ‘You have come here with far too much “baggage”’ she said. ‘You want to know; you want to understand. You are insisting that what is intended for you should necessarily come to you by the path which you have determined. Make yourself empty; simply be receptive: make your meditation one of pure expectation.’[14]

The monk redoubled his efforts:

Purusha went off to take tea with another European family. I excused myself on the grounds of my cold, and went back to the darshan, muffled up to the eyes. Did I really try to make myself empty on the lines suggested by Ethel? Or rather, did the fever which made me shiver get the better of all my efforts to meditate and reason? When the Vedas began again, their spell carried me off much further from things and from myself than had been the case on the previous evening. The fever, my sleepiness, a condition that was half dreaming, seemed to release in me zones of para-consciousness in which all that I saw or heard aroused overwhelmingly powerful echoes. Even before my mind was able to recognize the fact, and still less to express it, the invisible halo of this Sage had been perceived by something in me deeper than any words. Unknown harmonies awoke in my heart. A melody made itself felt, and especially an all-embracing ground bass... In the Sage of Arunachala of our own time I discerned the unique Sage of the eternal India, the unbroken succession of her sages, her ascetics, her seers; it was as if the very soul of India penetrated to the very depths of my own soul and held mysterious communion with it. It was a call which pierced through everything, tore it apart and opened a mighty abyss.[15]

[1] 'Swami Abhishiktananda', James Stuart, p.14

[2] Ibid, p.15

[3] 'The Further Shore', p.1

[4] 'Swami Abhishiktananda', James Stuart, p.21

[5] The Secret of Arunachala, pp.1,2

[6] Ibid., pp. 1,2

[7] Ibid., p.4

[8] Ibid., p.4

[9] Ibid., p.5

[10] Ibid., p.6

[11] 'Ascent to the Depths of the Heart', 24 January 1949

[12] Ibid., p.7

[13] Ibid., p.8

[14] Ibid., p.8

[15] Ibid., p.9