Table of Contents

Introduction to this issue

Calendar of Ashram Events

In Profile: Swami Abhishiktananda (part.II)

Announcement: In Focus

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Mahapuja Day

Sri Bhagavan’s Ayurvedic Recipes

Ramana Reflections: Winnowing the Chaff of the Heart

Bhagavan and Cinema: Mirabai

Sadhu Natanananda’s Upadesa Ratnavali

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Natarāja Puja

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Ashram Veda Parikshā

Obituary: Sri Vempuluru Venkata Rathnam

Events in Sri Ramanasramam: Cow Lakshmi's Samadhi Day

Dear Devotees, The Ashram regrets to announce the demise of Sri Rathnam, aged 68, who passed away on Sunday morning, the 25th June after 48 years in Tiruvannamalai and Ramanasramam (see obituary).

In this issue, we continue the life story of Swami Abhishiktananda from the May issue. The monk came to Bhagavan in January 1949 with a keen eye and a gift for writing, bearing inspiring testimony of his experience at the feet of Sri Bhagavan in the late 1940s.

In this issue we consider what it would be like to imitate Bhagavan and try and develop some of his qualities in a piece called, Winnowing the Chaff of the Heart.

Last month devotees edited, subtitled and uploaded two of the seven films that Bhagavan saw in the Ashram Dining Hall. In this issue we add the attached link for the newly uploaded imovie Mirabai. For videos, photos and other news of events, go to https://www.gururamana.org/ or write to us at <saranagati@gururamana.org>.

In Sri Bhagavan,

Saranagati

In Profile

Swami Abhishiktananda (pt. II)

continued from part 1 of the May 2023In the first segment in the May issue we saw how Abhishiktananda came to India and made his first visit to the Maharshi. He had high expectations about what the experience would mean for him. Even while still at the monastery in France he had heard and read about the Maharshi and dreamed of making the visit to Ramanasramam one day. The encounter held many surprises, not least of all, his first reaction which turned out to be one of indifference was linked to romantic assumptions he held about what it would be like to be in the presence of the Satguru:

When I come in, Bhagavan is reading his mail. If I had hoped to meet a perfect inhabitant of the other world, I would have been greatly disappointed. I could see for myself and was also told that Bhagavan has passed the stage of ecstasy. Henceforth he was able to attend to the details of daily life without the concentration of his thought on the Self being impaired to the slightest extent. He concerned himself with all the details of the Ashram, especially perhaps with those of the kitchen. We later saw him eating with an excellent appetite and lightly discussing the quality of the buttermilk with the dining hall server. Not long ago he could be seen in the kitchen in the early morning cleaning the vegetables. He keeps an eye on the work of the ashram, insisting on attention to details and the completion of a job, for example, in the bindery. Thus, we saw him reading his mail, correcting the proofs of books, telling what answers to give, reading a newspaper – The Hindu, if I am not mistaken. (Bhagavan can understand and read English very well, even though he usually only speaks in Tamil.) In the afternoon he enjoyed listening to the radio for some time (that day it was broadcasting Tamil songs). But there is nothing to watch apart from Bhagavan.[1]

This French monk had anticipated some transcendent transformational exchange between himself and the Master, but upon entering the hall, found things very calm and ordinary:

No words had been exchanged between the Sage and the man from beyond the seas. The Maharshi remained too distant for him to reach. He was separated from the crowd and from the enthusiasm of the devotees by the sanctuary with its oil lamps and dishes of incense, not to mention the disciples who took turns to serve him and remained constantly at his side. At that time [the Maharshi’s latest visitor] he was still too fresh from Europe. He did not know the language, and above all he had not yet sufficiently penetrated the inner world to be capable of directly understanding the mysterious language of silence.[2]

Everything was altogether novel to Abhishiktananda, and he took in what he saw, as best he could, not always able to work out its meaning.

Ethel Merston, whom he had befriended, chastened him about his preconceived notions and gave him pointers on how to approach the Maharshi. Whether it was due to her wise counsel or that enough time had passed to settle in a little, this second encounter with the sage proved very different:

Even before my mind was able to recognize the fact, and still less to express it, the invisible halo of this Sage had been perceived by something in me deeper than any words. In the Sage of Arunachala of our own time I discerned the unique Sage of the eternal India.[3]

The experience of this second meeting was so intense that the new arrival fell sick. If something was at work in him below the threshold of consciousness, a forty-degree fever suggested some alchemical reaction where former impurities might be purged by fire before the aspirant could come to know and see the Maharshi truly. Already on this first night, his vision changed, and he discerned in Bhagavan Ramana "the unbroken succession of India’s sages, her ascetics, her seers". Bhagavan appeared to him ‘not as a dead man come back to life’, but of ‘a (so-called) mortal who possessed being in his inmost depths’. He adds, ‘this being can never be taken away by any power whatever, whether of nature or of will.’[4]

Unfortunately, the planned week-long stay was cut short owing to the fever. Not wanting to be a burden to anyone, he made the sudden decision to depart for Trichy:

By the evening I knew that I had to leave. The fever was getting worse, and it would have been impossible to burden the ashram with an invalid when there was such a flood of visitors. Again, the half-hour of jolting in the bullock-cart, an exhausting night on the train, in crowded compartments, when twice I had to change trains... A very hard night in the train. All my dreams about Ramana. Next morning, I simply fell into bed and stayed there for three days, unable to move. But if the body was stretched out under the bedclothes, the spirit was still at Sri Ramanasramam.[5]

He still had not connected the fever with the encounter that had occurred in the hall and took his condition to be an ordinary fever. During his convalescence, he struggled to make sense of what was going on within him. He later wrote of the change he had undergone:

There is one fact which determines everything: the religious experience which I had on non-Christian ground with an intensity never even glimpsed until then, but which was in line with all that I had obscurely felt before. Ramana’s advaita is my birthplace, the original womb [mulagarbha]. Against that, all reasoning is shattered. And I have always hesitated to take the decisive step in which I have always felt that final peace and joy would be found.[6]

Though conventionally speaking Abhishiktananda was struggling with the effects of a virus, the true virus was the cognitive dissonance born of encountering clarity beyond what he had ever before known and the contrast to all that he theretofore called religion which was now set alongside a direct experience of the divine. He was thus compelled to build a bridge between what he had till then known as faith and the advaitic experience at the Feet of Sri Ramana:

The Christ, whom I first knew and loved in his historical life in Jesus, and then in his epiphany in the Church, (...) has appeared to me in the form of Bhagavan Sri Ramana. Seated on the lotus, at the centre of my heart, all my efforts aim at finding this centre of myself, which is he, Abhishiktesvara (‘lord of the anointing’) in the form of the Maharshi. To find in the depths of myself that Siva Shanta advaita [grace, peace, non-duality] that Bhagavan is. Not the Bhagavan that I have venerated and before whose image his disciples prostrate, but the Bhagavan that I am in all reality at the source of myself.[7]

In the days that followed the monk struggled to get his bearings, but his mind and heart were stunned by the meeting. He put forth no small amount of energy in making sense of the path ahead:

To go within by means of the idea of the within is a good way. However, the idea of the within is distinction (bheda). If I distinguish the within from myself who seeks the within, I am not within. He who seeks and that which is sought vanish in the last stage, and there is nothing left but pure light, undivided, self-luminous (jyoti akhanda svaprakasa). The last work to be done is to cut through the final distinction between he who seeks and that which is sought. That is the knot of the heart (hridaya granthi). And Ramana was right in recommending the annihilation of the very thought of myself, which is the source of everything else.[8]

How to square the lucidity of this new world that was dawning upon him since the visit to Ramanasramam with the former world he had come to call his own? The former ignorance, as it were, was coming to a head like a boil and bursting open to release its unwanted contents, both painful and disruptive but cathartic. His head swirled as he lay on the sickbed in Trichy, reliving the days at Ramanasramam:

In my ears the Vedic chants, as I heard them there, continued to sound. Before my eyes still danced the picture of the old man stretched out on his couch and of the crowd which pressed devotedly round him. In my feverish dreams, when I was neither fully awake nor fully asleep, it was the Maharshi who unremittingly appeared to me, the Maharshi accompanied by all the sages and all the gurus, the Maharshi bringing the true India which no time can contain and of which he was for me the living and compelling symbol. My dreams included attempts – always in vain – to incorporate in my previous mental structures without shattering them, these powerful new experiences which my contact with the Maharshi had caused to spring up in me; new as they were, their hold on me was already too strong for it ever to be possible for me to disown them. When I came to myself again after those days of fever, I realized to what a depth in myself this first meeting with Sri Ramana had penetrated as part of the mystery of Arunachala.[9]

Time passed and duty called. Though the memory lingered, and his deepest longing was to get back to Arunachala, eight months would pass before he returned:

This time I had high hopes of spending at least one full week at the ashram. I came by myself, no longer encumbered with clothing brought from Europe, but with my loins girt and shoulders covered with long strips of cotton, after the custom of Tamil Nadu. I reached the ashram about midday. This was because the Trichy train had been running late, which caused me to miss the connection at Villupuram. Alas! I arrived at a bad moment. As I was not in correspondence with anyone at Tiruvannamalai, and besides very rarely read the newspapers, I was totally unaware of all that had been happening since my first visit.

Sometime in February a tumour had appeared on Sri Ramana’s left elbow. The doctors had removed it, but it came again, and a second operation also had failed to check its growth. The only sure remedy would have been to amputate the arm. But the Maharshi asked, “What is the use?”, and flatly refused to allow it. Then they tried all kinds of treatment – radium, herbal, homoeopathic, ayurvedic, siddha – each one as painful and as useless as the others. Only a few days before, the Maharshi had undergone a final attempt by surgical means, which had left him desperately weak. No one was allowed to come near him, apart from medical attendants.[10]

All this was explained to Abhishiktananda when he came to the ashram office. With no chance of having darshan, with the guesthouse closed until further notice, he resigned himself to return to Trichy:

Greatly put out, I could see only one course before me: to take the evening train and return when conditions were more favourable. However, before leaving I thought of seeing Ethel. ‘Even so you are not going to leave like this,’ she said at once. ‘You must certainly stay and see the Maharshi. I have no doubt that in two- or three-days’ time people will be allowed once again to have darshan. I have it on good authority that Bhagavan is insisting that he should not be kept in isolation like this. If the ashram refuses to put you up, I will make some other arrangement for you.’[11]

Ethel took him to the office and pleaded on his behalf. It was agreed that he could eat at the ashram. He was allowed to use a small lean-to in the courtyard of Mahasthan, the Bose compound, where Ethel was occupying one of the huts:

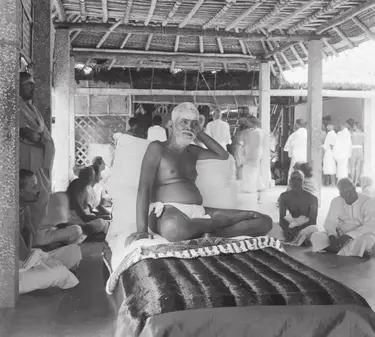

As it turned out, times for darshan began again on the very next day, though they were limited to an hour in the morning and another hour in the afternoon, during which the Vedas were chanted. The crowds were now greater than ever, as the news of the Maharshi’s condition had spread all over India, and from every direction people were hastening to have the darshan of the Sage. This time I was better prepared to profit from this blessed opportunity, and I did my best not to allow my efforts at rationalization any longer to obtrude themselves, as they had done on the first visit, but rather simply to attend to the hidden influence. The times for darshan being so restricted, I had plenty of free time. This gave me the chance to climb up to Skandasramam, to take short walks in the neighbourhood, and above all to talk with the Maharshi’s disciples.[12]

Ethel had come to be his protector and guide and was single-handedly responsible for his being allowed to stay on. In a spirit of gratitude, he lauded Ethel’s hospitality and solicitude:

Ethel was an Englishwoman, always ready to do anyone a kindness, no matter when or who it might be. This indeed she used to do with great sensitivity. I still remember how, several years later, one Christmas morning when once again I was staying in this lean-to in the Bose Compound, she quietly came to my door and left on the threshold a plate of chocolates and other delicacies, disappearing immediately so as not to interrupt my meditation and silence on such a day.... At my request she put me in touch with certain chosen disciples of the Maharshi. I thus had some excellent conversations with a young Telugu brahmin who, being unmarried, lived at Tiruvannamalai with his mother and was one of those who were privileged to minister personally to Sri Ramana. I asked him to explain to me the Maharshi’s teaching, and he did so to the best of his ability, in a very lucid fashion and using the philosophical terminology which at that time I found very congenial. But now, as I look back, I cannot help smiling gently at such attempts to define in intellectual terms that which by its very nature excludes the possibility of being reduced to ideas. But even so, we must recognize that this has to be the starting point for some. There are those who dive straight into deep water from the top of a boulder; while others walk slowly down the beach and only take short steps into the water which is calling them... Happy are they when a big breaker surprises them and gives them a dunking![13]

Abhishiktananda used this time of waiting to meet other of Bhagavan’s devotees. All were awaiting Bhagavan’s recovery and the resumption of darshan in the hall. The monk inquired of older devotees about their experiences and understanding:

I met another brahmin from the Andhra country, a much older man who was living in one of the Palakothu hermitages. He was not particularly learned or intellectual, but what he said to me seemed to spring directly out of his very deep personal experience. One evening he came to look for me at Bose Compound and we sat together on the great stone bench facing the Mountain. He told me about Sri Ramana’s illness, the very painful operations which he had to undergo and the marvellous indifference with which he bore his sufferings, even when his face betrayed the torments which racked his body. “He made me think of the Lord Jesus,” was his comment. But the Maharshi had absolutely no concern for his body. He allowed the surgeons to cut it about as they pleased, and very unwillingly accepted their decisions about the rest which he was supposed to take, of the seclusion which they imposed on him, and of the special food which was dictated by his condition. According to this disciple, the most central point in Sri Ramana’s teaching is the mystery of the heart, of which the best treatment is that by Ganapati Sastri in his Sri Ramana Gita. Find the heart deep within oneself, beyond mind and thought, make that one’s permanent dwelling, cut all the bonds which keep this heart at the level of sense and outward consciousness, all the fleeting identifications of what one is with what one has or what one does. He quoted and then copied out for me a marvellous verse from the Mahanarayana Upanishad (12.14): ‘Heaven is within the inner chamber, the glorious place which is entered by those who renounce themselves!’[14]

After having resumption of darshan, Abhishiktananda got to see the Maharshi. When his one week was over, he returned to Trichy to take up his work there. He became occupied with the founding of Shantivanam, the hermit Ashram along the Kaveri River near Kulithalai, about 30 kms from Trichy.

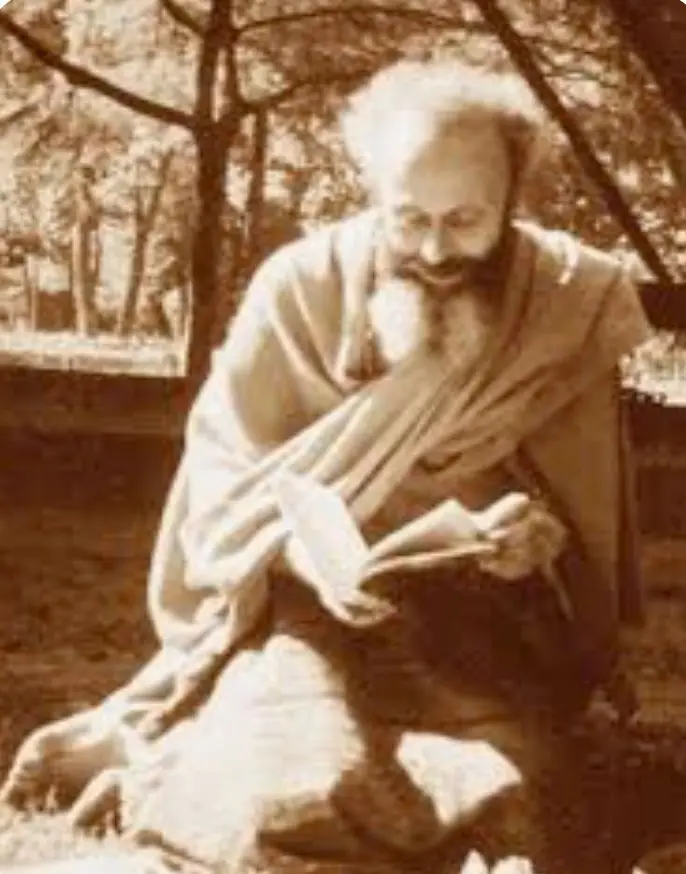

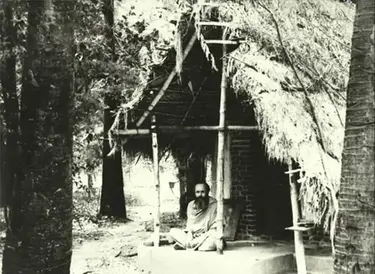

Along with Purushananda, the two made up their mind to model their community on simplicity and to live in no more comfort than the village poor in the nearby Thannirpalli. Thus, they constructed simple bamboo huts with grass roofs, unscreened windows and sandy dirt floors. They allowed themselves one luxury, namely, a bed of loose bricks, one laid next to the other. They found that their brick beds attracted eight legged visitors, which included scorpions seeking shelter in between the cracks in the bricks. Committed to simplicity, they surmounted their desire for bodily comforts by remembering that everyone around them suffered similar privations. Abhishiktananda lauded his companion, Purushananda who was ‘permanently lost in the higher spheres’ and who in all earnestness had complained to Abhishiktananda about their huts being ‘too spacious and almost luxurious’ (23.3.50)[15] Abhishiktananda’s biographer comments:

It was natural that they should desire to keep the ashram as simple as possible, and to practise a poverty that was more radical than the formal ‘poverty’ of western monasticism. Their poverty was an expression of the ideal of sannyasa, and at the same time, identification with [the village] poor.[16]

When construction was completed in late March, Abhishiktananda, made plans to return to Ramanasramam:

I had made up my mind to return in the spring of 1950. Sri Ramana had been near death for several months. They wrote from the ashram that he might leave his body at any moment, or equally might continue living indefinitely. All depended on his decision. He would withdraw once his mission was fulfilled, but he had not told anyone what he had decided. Everyone was in suspense. Purusha had seen him not long before – no longer indeed in the great hall of darshan, but through the window of his small room, as one of the crowd of pilgrims who filed slowly past, gazing for the last time at the face of him who had penetrated the great mystery. To Purusha it seemed that Sri Ramana’s eyes had rested on him, and he treasured as a unique blessing the grace of this final look.

I was thus planning to leave Kulittalai on a certain Monday; but two days before, when I opened a Tamil newspaper, I read there to my sorrow that on the previous evening, Friday April 14th, Sri Ramana had attained Mahanirvana. The same paper mentioned the beam of light which had trailed across the sky at the precise moment of his passing and was observed by disciples who lived far away from the ashram, even some of them as far as Madras, totally unaware that at that very moment Sri Ramana was leaving this world. The Maharshi was no longer there, and any desire to return to Tiruvannamalai at once left me.[17]

However, towards the end of the following year, when some European friends asked him to join them on a brief pilgrimage around Tamil Nadu, he suggested they go to Tiruvannamalai. It was not clear if they would be allowed to stay at the ashram, given ‘the problems of succession’ there but what happened was quite the reverse:

Swami Niranjanananda received us most cordially, we were given a very comfortable room and, when we left, they refused to accept a single penny for our three days’ stay. I was much moved, as I revisited all the places where the Maharshi had lived, I remained for a long time seated in the northern veranda of the Temple, near the samadhi where rested his mortal remains. I was particularly happy to meditate in the small room where he had passed the last months of his life and where he drew his last breath. Here were collected some books and other objects of his personal use. Every morning and evening the Vedas were sung in front of his tomb, just as had been the custom during his lifetime, and at the same hours. Once again, I felt their spell. This time I was especially impressed by the final chant, one of the Maharshi’s own compositions in Sanskrit called Upadesha Saram, which followed the psalmody of the Taittriya Upanishad and the Rudram from the Krishna Yajur Veda. When the singing ended, the priests of the ashram solemnly offered puja first at the samadhi, then at the temple of Sri Matrubhuteshvar, then at various places in the ashram where Sri Ramana had lived and given his darshan, and finally in the small room of his Mahanirvana, where he renounced for ever all manifestation under conditions of space and time.

Abhishiktananda continues to describe the ashram and the changes:

At the entrance to the temple was the great mantapam, so lacking in atmosphere, where Sri Ramana had been installed during his last months for the daily darshan. Here they had erected a life-size statue of the Maharshi in stone. But alas, the sculptor of Elephanta or of Elora would have been needed to breathe into the granite something of that inward look which was characteristic of the Sage! Even the highest human art, if not inspired by an inner vision, could never succeed in expressing that ‘unique presence of the self within the self.’ Above the statue and the ceremonial couch – this also in granite and decorated with lions’ heads – was engraved in letters of gold on a black background the marvellous Sanskrit sloka in which Sri Ramana had summed up his whole experience and which Sri Ganapati Sastry embodied in his Sri Ramana Gita: In the midst of the cave of the heart, in form of the I, in form of the Self, unique and solitary, Brahman’s glory shines directly from Himself on Himself. Penetrate deep within, your thought piercing to its source, your mind immersed in itself, with breath and sense held close in the depths, your whole self fixed in yourself, and there, simply BE![18]

Announcement: Sri Ramanasramam’s In Focus

Please see the monthly video series, In Focus featuring daily life at Sri Ramanasramam: For the month of May, and the month of June.

Mahapuja celebrations commenced on the morning of the 12th June with mahanyasa japa in the Mother’s Shrine elaborately adorned with flower festoons and other decorations. Live online streaming allowed devotees around the globe to hear songs like Manavasi Iyer’s Matrubhuteswaram, Muruganar’s Katthāya, Ganapathi Muni’s Dundubhi Varshe and Panjamma’s Ashagannai yārena, sung by RMCL, Bangalore as well as a song from KVS, his Sundaran Nayakiya. The celebration culminated in Deeparadhana around 10.30 am. Dr. Ambika Kameshwar gave a concert dedicated to Alagammal on Saturday evening, 10th June in the Grantalaya auditorium.

Ramana Reflections

Winnowing the Chaff of the Heart

Beyond Bhagavan’s innumerable divine qualities, devotees ever marvelled at his gentle caring nature and the impeccability he demonstrated throughout his earthly life. In addition to his boundless wisdom, Bhagavan’s uprightness in conduct, honesty in speech, his unassuming nature free of the need to craft any image of himself, his ability to allow himself to be scrutinised by others without needing that their perceptions of him be one way or the other, and his capacity to listen and empathise fully with the suffering of a mother who had just lost her only child stand out as truly remarkable.

As devotees, we are called to imitate Bhagavan as much as possible. But when we look at this vast array of cherished character traits, it is hard to imagine how we could ever undertake such a task. Is it not that Bhagavan is Bhagavan and no amount of effort on our part can help us to be like him?

It has been said that dharma is only dharma when we put it into practice. Understanding Bhagavan’s teaching requires effort but seeking to be like him is a superhuman endeavour. If most of us are content with devotion to Bhagavan and letting him take care of the rest, at least this is the beginning of discipleship. But to receive his grace in full, we must find ways to take on some of the qualities he demonstrated day in and day out if ever there would be space in our hearts for his grace to enter in and take root:

God is in all and works through all. But His presence is better recognised in purified minds. Pure minds reflect God’s actions more clearly than impure minds ... When ‘mine’ is given up, this is chitta suddhi (purified mind). When ‘I’ is given up this is Jnana.[19]

Hearing Bhagavan speak about our purity is daunting because many of us imagine there is little chance that purity could ever be brought about in us. Purity after all is like innocence, is it not? You either have it or you don’t, right? But Bhagavan didn’t see things this way. For him, every heart is pristine in its essence and every defilement that obscures the pristine heart comes from without in time and therefore can be gotten rid of in time. So what blocks the path to purity? Bhagavan comments:

Thoughts are only vasanas (predispositions), accumulated in innumerable births. Their annihilation is the aim. The state free from vasanas is the primal and eternal state of purity.[20]

Tradition speaks of two pivotal practices that prepare the mind for eliminating vasanas, namely, clean conduct and non-indulgence in worldly enjoyments. For Bhagavan it was assumed that devotees in his midst had gotten good training in conduct. This would have been a reasonable assumption in Bhagavan’s time. But in the current generation where the complexity of the modern world impinges on every aspect of our lives, stealing away our attention from the habits of mind and body, it is not clear to what extent dharma is still fully intact. It is also not clear if we are getting ongoing dharmic training in the way, say, our grandparents would have gotten. Words like ‘duty’, ‘morality’ and ‘virtue’ have fallen away from the common parlance in the 21st century simply because we are unable to meet the standards of former generations. Why? Because ethical life is context dependent whereas digital isolation born of the information age disrupts social and community bonding. Such disruption, researchers point out, is not merely social and cultural but neurological, impairing our ability to relate to others and empathise with them.

To make matters worse, the volume and intensity of sense stimulation in the information age is far beyond anything previous generations had to contend with. If traditions over the centuries struggled to keep pace with cultural and technological innovation, the pace of change in the digital 21st century has accelerated beyond all imagining. Never at any time in human history have the six senses been so outwardly drawn:

To make matters worse, the volume and intensity of sense stimulation in the information age is far beyond anything previous generations had to contend with. If traditions over the centuries struggled to keep pace with cultural and technological innovation, the pace of change in the digital 21st century has accelerated beyond all imagining. Never at any time in human history have the six senses been so outwardly drawn:

Because your outlook has been outward bent, it has lost sight of the Self and your vision is external. The Self is not found in external objects. Turn your look within and plunge down[21]... [True] pleasure consists in turning and keeping the mind within; pain in sending it outward. There is only [true] pleasure. Absence of pleasure is called pain. One’s nature is Bliss (Ananda).[22]

Turning our attention inward means taking stock of conditions within and without. Making ourselves fit vessels to receive all that Bhagavan is offering us means figuring out how to be less aversive toward self and other, learning how to identify unwholesome impulses within and avoiding pretending they are not there. Here we look closely and allow the light of awareness to shine on them. If we see that the intentions undergirding our actions and words are at variance with what we want others to believe about us, we also take notice of the inclination to conceal them altogether.

We take up this task avoiding every hint of self-blame, judgementalism or moralistic self-criticism. We call on Bhagavan to help us be patient with ourselves as we undertake this sensitive work.

If till now we had assumed that inner cleansing required some pre-existing purity from former births, we now accept that progress on the path can only come about through intentional efforts in the present. If formerly we thought good conduct hinged on keeping up appearances, now we see that it begins by taking stock of all that is not complete within us. We begin to see the advantages of abandoning our vanity projects and learn to ferret out the impulse to embroider our self-image. In short, we look for the merest inclination to appear as more than what we are and instead, learn to accept ourselves as we are, imperfect, no doubt, but nevertheless sincere in our intentions.

Namaskaram in the Darshan Hall

Once in the late 1930s, Bhagavan called devotees out for their lack of earnestness in respect of their prostrations which had become mechanical at best and at worst, appeared as counterfeit:

Namaskar was originally meant by the ancient sages to serve as a means of surrender to God. The act still prevails but not the spirit behind it. The doer of namaskar intends to deceive the object of worship by his act. It is mostly insincere and deceitful. It is meant to cover up innumerable sins. Can God be deceived? A man thinks that God accepts his namaskar and that he himself is free to continue his old life. People should keep their minds clean; instead of that, they bend themselves or lie prostrate before me.[23]

Bhagavan’s words sound sharp, but he is only trying to shake us free of the delusion that traps and oppresses us. Bhagavan is not the stern father seeking to punish us but is only seeking to get our attention that we might make progress. If Bhagavan was mostly tolerant with our less-than-perfect piety, he also knew that if the work of inquiry was to become thoroughgoing and honest, we would have to learn to identify the subtle dissonances of the heart born of karmically generated volitions. He knew we had to cross this threshold if ever we were going to integrate the deeper dimensions of the teaching.

When we recall the young Bhagavan at Patala Lingam in the winter of 1896, we see someone in the highest stage of samadhi where all mental activity was suspended – even to the point that bodily functions were attenuated. Those in the presence of one thus absorbed were often not even sure if he was alive.

Why would the tradition extol such a state? Because it is believed that in this stage the heart comes to rest forever in its own being and every last trace of worldly accumulation is rooted out once for all.[24]

As ordinary devotees, we may not even aspire to such advanced stages of spiritual practise if for no other reason than life makes too many demands on our time. But whatever efforts we put forth in following Bhagavan’s path, we are being asked to maximize them by sticking close to practices that bring beneficial results. When we look out into the world, we see misunderstanding everywhere. We also see that not every spiritual discipline is efficacious. Consider Himalayan ascetics of the past who had taken it as their chosen sadhana to stand on one leg or to hold up one arm in the air for years on end. No doubt such practices help cultivate determination, endurance and patience but do they purify the heart, heal karmic affliction, make us better human beings and lead to Bhagavan’s wisdom? The answer is, probably not. If they did, Bhagavan would have assigned us such tasks. The false-hard way is actually easier than giving up treasured attachments. Letting go of what we cling to is more difficult than any physical exertion. If we are truly going to follow Bhagavan, we have to be honest in our inquiry every step of the way in Bhagavan’s steep path of seeing through the wily ways of the ego and its unwholesome strategies.

Invariably, Bhagavan’s way entails learning how to be clean in conduct. Karma-purifying vichara is the principal means by which we chip away at what is not true in us. Bhagavan was not just asking us to avoid pretense and affectation, but to examine ourselves so thoroughly that we might uncover every last trace of self-partiality and thereby diminish unwanted thoughts and undulations in the mind:

The mind is like akasa (ether). Just as there are objects in the akasa, so there are thoughts in the mind. The akasa is the counterpart of the mind and objects are [the counterparts] of thought.As we become clear about the incentives behind our thoughts, words and deeds, the mind becomes cleaner by virtue of the honest attention we give it. For the first time we learn how to rest in our own heart and cultivate the silence Bhagavan prized above all accomplishments. Winnowing chaff from the heart just means getting rid of what ails us, even if we are clinging to it. If such winnowing is only the first stage in becoming Bhagavan-like, the joy it brings is unparalleled. The peace of a heart no longer conflicted and a mind no longer needing to second-guess itself is a milestone. The ability to sit with oneself unburdened by inner entanglements and the compulsion to be somewhere else is an important juncture, inspiring us to take up Bhagavan’s teaching with ever increasing vigour. The undulating mind (i.e., mind associated with rajas or activity, and tamas or darkness) is commonly known as the mind. Devoid of rajas and tamas, it is pure and self-shining. This is Self-Realisation.[26]

As we become clear about the incentives behind our thoughts, words and deeds, the mind becomes cleaner by virtue of the honest attention we give it. For the first time we learn how to rest in our own heart and cultivate the silence Bhagavan prized above all accomplishments. Winnowing chaff from the heart just means getting rid of what ails us, even if we are clinging to it. If such winnowing is only the first stage in becoming Bhagavan-like, the joy it brings is unparalleled. The peace of a heart no longer conflicted and a mind no longer needing to second-guess itself is a milestone. The ability to sit with oneself unburdened by inner entanglements and the compulsion to be somewhere else is an important juncture, inspiring us to take up Bhagavan’s teaching with ever increasing vigour.

Sadhu Natanananda’s

Upadesa Ratnavali

In telling the life story of Dorab Framji in the June issue of Saranāgatī, there were various references to Sadhu Natanananda (Natesa Mudaliar, 1898-1981) and his published works. Since manuscripts still exist, we reproduce this English translation of the first stanza of his yet-to-be-published 'Upadesa Ratnavali'.

Because the true meaning of ‘I’ is always Siva swarupa, of the nature of undivided Being-Consciousness-Bliss, he never comprehends external objects. Why? Because knowing and making known are not the nature of Being-Consciousness-Bliss nor the true ‘I’. Any object seen at any time according to the standpoint of the highest truth (paramarthika sathya) is only ‘God’, and according to the truth of the world (vyāvahārika satya), God is seen ‘first’. How?

The one and only existing entity of the nature of Being-Consciousness-Bliss, according to Jnanis, is God. From the standpoint of pure advaita, consciousness-space (chidākāsa) contains no difference between seer, sight and object seen (triputtis). So, sight here is of the nature of seeing oneself only, i.e. being the Self. This forms the established verdict according to the highest truth (pāramārthika satya).

If asked how it is that we see time-bound objects with ‘names and forms’ in front of us, it is because names and forms are insentient (jada). They shine forth only by the light of the Atman. Only after the removal of darkness by light can any object be seen. First the light has to be comprehended which is the nature of God before we can see objects. This is the meaning of ‘seeing God first’. This is the verdict according to the truth of the world (vyaavahaarika satya).

On morning of 26th June, Vedic students gathered at the shrine of Lord Natarāja accompanied by Ashram priests to recite the Rudram during abhishekam for the puja of the Lord who is Creator, Preserver and Destroyer.

Sri Ramanasramam is one of only a handful of Veda parikshā centres in South India. On 26th June, eighty Vedic students came from all over South India to undergo three days of examinations in Krishna Yajur Veda. Mulam, Samhita, Padam, and Kramam in Krishna Yajur Veda were among the examinations given.

Scholars in ancient times sought to preserve the sanctity of the sastra and therefore devised various paathas or modes of recitation to guarantee accurate transmission down through the generations. Parikshā is the means of ensuring that such paathas are faithfully retained. In all, about 75 certificates were awarded by Ashram President, Dr.Venkat S.Ramanan at the conclusion of the examinations on Wednesday evening, 28th June

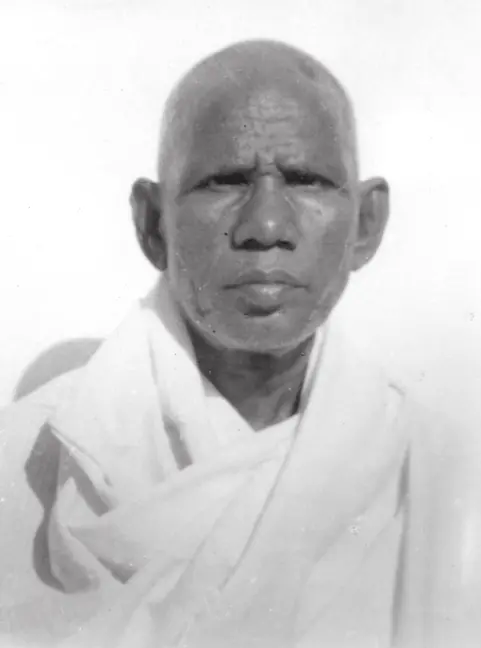

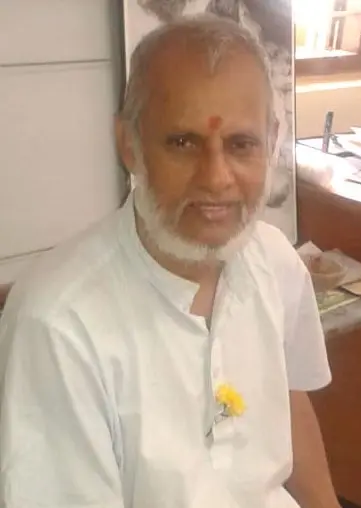

Born 2nd October 1954 to Venkaiah and Krishnamma as the second of seven children in Gudur, Tirupati district, Sri Rathnam came to Tiruvannamalai as a 21-year-old in 1975. During his first two years he lived with Lakshmana Swami who also hailed from the Gudur-Nellore area. He also resided for a period with Bhagavan’s old attendant, Krishaswami. As a sadhu, Rathnam was helped by devotees in Tiruvannamalai for his basic needs and in the late 1980s, one devotee gave him a piece of land. In the mid-1990s, he took a room in Annamalaiswami’s Ashram and subsequently in Ramanasramam.

For the past 25 years Rathnam was in charge of the Ashram bookstall photo department and helped devotees with special large photos. For a number of years, Rathnam also took care of Bhagavan’s Old Hall. Each evening after closing time he cleaned the hall with sincere devotion. He also had permission to sleep alongside Bhagavan’s sofa, just as a handful of devotees had done in Bhagavan’s time. One of his spiritual disciplines was remaining within the confines of the Ashram and thus for years at a time, he would never pass through the front gate. Thirty years back, Dennis Hartel published the following description of Rathnam in 'The Maharshi':

Never did I see him speak to anyone unless he was spoken to, and this I saw on only two occasions. Never did I see him idle for a moment. In the early mornings until breakfast he would remain in the Old Hall in prayer and meditation; in the afternoons and nights I would see him sitting in the Samadhi Hall. For many hours each day, in a consistent manner, I saw him sitting in prayer and meditation. If he moved about, it was only to attend the pujas in the Mother’s shrine and to ring the bells at Bhagavan’s shrine during worship. His whole life is directed to Bhagavan and his sadhana. He is a rare example of one-pointed dedication and devotion, an invaluable asset to the ashram, and an inspiration for all.

On the morning of 25th June, Rathnam merged at the Feet of Bhagavan in his Ashram room near the Vedapatasala. He is survived by his two adoring sisters, K.Jyothi and Y.Prameela, and his many nephews and nieces.

Cow Lakshmi came to Bhagavan as a young calf in 1926. Initially tended by a caretaker in town, she used to walk from town each day and spend the day with Bhagavan. Upon her arrival in the Ashram, she would enter the hall and, when seeing Bhagavan, prance about with demonstrable joy. When she became pregnant with her first calf, Bhagavan asked that a shed be constructed for her in the Ashram. During the course of the next 22 years, Lakshmi gave birth to nine calves, three of which, remarkably, were born on Bhagavan’s Jayanthi Day and others born on Bhagavan’s monthly Punarvasu Day. This year on Saturday, 30th June, her Samadhi Day was observed with a special puja at her shrine. Devotees chanted Bhagavan’s Tamil and Telugu venbas which confirm Lakshmi attaining Mukti (liberation) and then sang

Manavasi Ramaswamy Iyer’s long poem on Lakshmi hailing her journey into Bhagavan’s heart.

At the end of

the function,[27]

Dr.Ambika Kameshwar led the group as everyone sang KVS’s lullaby to Cow Lakshmi.

[1] Ascent to the Depths of the Heart, p.9

[2] Guru and Disciple, p.11

[3] The Secret of Arunachala, p.8

[4] Ascent to the Depths of the Heart, 10 Dec 1959, p. 225

[5] The Secret of Arunachala, p.9

[6] Ascent to the Depths of the Heart, 4th Sept 1955, p.122

[7] Ibid, 28th Oct 1955, p.129

[8] Ibid, 6th March 1956, p.146

[9] The Secret of Arunachala, p.9

[10] Ibid, p.10

[11] Ibid, p.10

[12] Ibid, p.11

[13] Ibid, p.13

[14] Ibid, p.13

[15] Swami Abhishiktananda, James Stuart, p.37

[16] Ibid, p.39

[17] The Secret of Arunachala, p.19

[18] Ibid, Ch.2 v.2; pp.20-21

[19] Talks, §594, §581

[20] Talks, §80

[21] Talks, §238

[22] Talks, §244

[23] Bhagavan’s comment also includes: They need not come to me. I am not pleased with these namaskars ... I am not deceived by such acts – Talks, §549

[24] This kevala nirvikalpa samadhi (what the Buddha called nirodha sa- mapatti) became permanent in Bhagavan, i.e. sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi.

[25] Talks, §485

[26] Talks, §100

[27] The Gopuja ceremony can be viewed on https://youtube.com/embed/5OviyaBUDP4